NOAA and partners assess reef, aid recovery following Hurricane Irma

January 2018

Within days of Hurricane Irma crossing the Florida Keys on Sept. 10, 2017, NOAA managers and scientists, partner agencies and local organizations launched an unprecedented effort to rapidly assess sections of the reef tract and conduct coral rescue and stabilization. Although a natural process, the widespread nature and strength of the hurricane, combined with the overall conditions of reefs in the region, prompted an aggressive response.

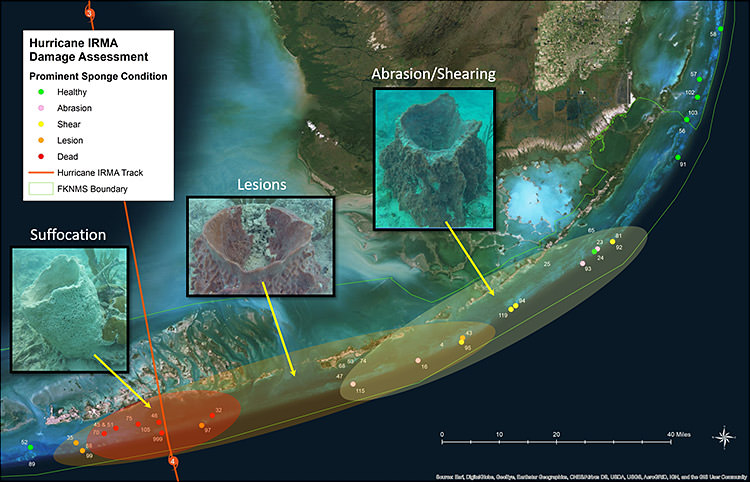

The type of damage and severity varied across the reef and even within assessment sites. In the hurricane's direct path through the Middle and Lower Keys, divers found fracturing and eroding of the coral reef framework. Heavy sedimentation and lingering turbidity slowed recovery and exacerbated preexisting conditions such as coral disease and bleaching. Additionally, high wave energy and choking sands caused unexpectedly high levels of sponge mortality in some locations.

"Although the assessment and recovery efforts reached only a small portion of Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, they were focused in more than 50 high-value sites including healthy and diverse areas, those with threatened coral species, and areas where research and monitoring histories offer comparative data," said Sarah Fangman, sanctuary superintendent. "Of course, the mission also targeted sites important for recreational and commercial use as well as managed zones within the sanctuary."

Coral reefs stretch south from Miami to Key West, and continue to the Dry Tortugas. In the Florida Keys (Monroe County), reef-based recreation and tourism are a significant part of the economy, supporting more than 33,000 jobs and generating $2.3 billion in annual sales.

Dr. Steve Gittings, chief scientist for NOAA's Office of National Marine Sanctuaries, said immediate responses, including unburying, repositioning, reattaching and stabilizing corals, offered a greater chance for recovery, particularly for rare species.

However, he said storms serve a purpose by creating new shelter and food for reef creatures other than corals. At most surveyed sites, corals were left in their post-hurricane position.

"While it feels good to upright a coral, we have to be selective," Gittings said. "I turned over one toppled coral only to find three sea urchins, two brittle stars, and a fish, all feeding on the decaying tissue under the colony."

During the assessment, a Unified Command led by the Coast Guard and supported by the sanctuary identified nearly 1,800 damaged and derelict vessels that pose environmental and navigational hazards. Most were removed by their owners but a few hundred remain.

However, marine debris remains an issue. Florida Keys fishermen estimate losing 150,000 lobster traps, many of which will continue to ghost fish until they are retrieved or rot and fall apart. Other marine and household debris litters the sensitive ecosystem.

Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, with its many partners, continues to evaluate storm impacts to inform management decisions and potential updates to existing regulations and marine zones that are designed to protect resources while allowing for sustainable use.

The rapid assessment and recovery missions involved multiple NOAA programs: Office of National Marine Sanctuaries, Fisheries Habitat Conservation, Restoration Center and Southeast Regional Office, National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science, and the Office for Coastal Management's Coral Reef Conservation Program. Additional partners included Florida Department of Environmental Protection, Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, National Park Service, Nova Southeastern University, Coral Restoration Foundation, The Nature Conservancy, Florida Aquarium Center for Conservation, Mote Marine Laboratory, Force Blue, and the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation.