Response

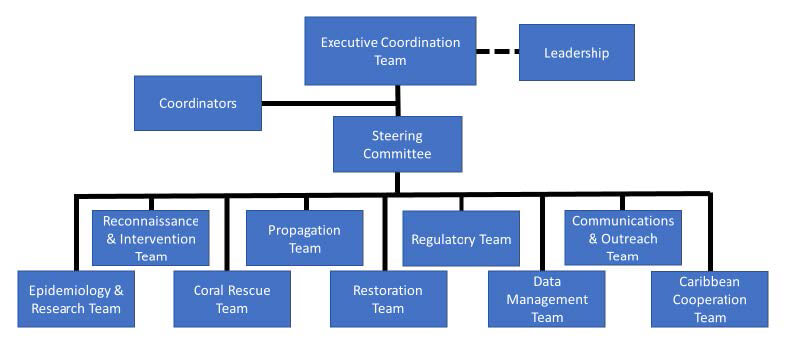

Due to the severity and longevity of this coral disease outbreak, a response has coalesced among management authorities, researchers, conservation practitioners, non-governmental organizations, veterinarians, and engaged citizens. Roughly 60 partner organizations participate in nine response teams, each focused on a different priority topic area. The response is led by two bodies: a Steering Committee and an Executive Coordination Team.

Investigation

Why it is difficult to determine a cause

Corals contain an assemblage of microbes and algae co-existing as a complex system, which makes the identification of disease pathogens an intricate task. Additionally, corals are in an open system – the ocean – with constant input of microbes from the environment, further complicating the investigative process.

Bacteria can be a primary pathogen, a secondary pathogen creating a secondary infection in unhealthy corals, or an opportunistic pathogen attacking corals with depressed immune function. Some of these pathogens may be normally associated with corals and are harmless until triggered by an environmental change. The relatively new scientific field of coral disease has identified only about a dozen pathogens in the world.

Current hypotheses include that secondary pathogens are influencing the virulence of stony coral tissue loss disease, while nvironmental factors may be affecting disease progression and transmission. Experiments are ongoing. The identification and isolate of the pathogen(s) causing stony coral tissue loss will be important for the development of diagnostic tools and more targeted treatments.

Pathogen Research

Research continues into finding the pathogen responsible for the stony coral tissue loss disease impacting Florida's Coral Reef. While the exact pathogen remains unknown, laboratory studies by Dr. Blake Ushijima of the Smithsonian Marine Station and field observations by coral ecologist Dr. Greta Aeby of the University of Qatar, suggest that multiple microorganisms may play a role. They think it is likely that an initial pathogen attacks the healthy coral and opportunistic pathogens then accelerate the disease. These infections appear as different lesions on the coral. The pathogen(s) is known to spread through direct coral-to-coral contact as well as through ocean currents. Dr. Ushijima continues to search for the pathogen and Dr. Aeby is examining other modes of possible infection.

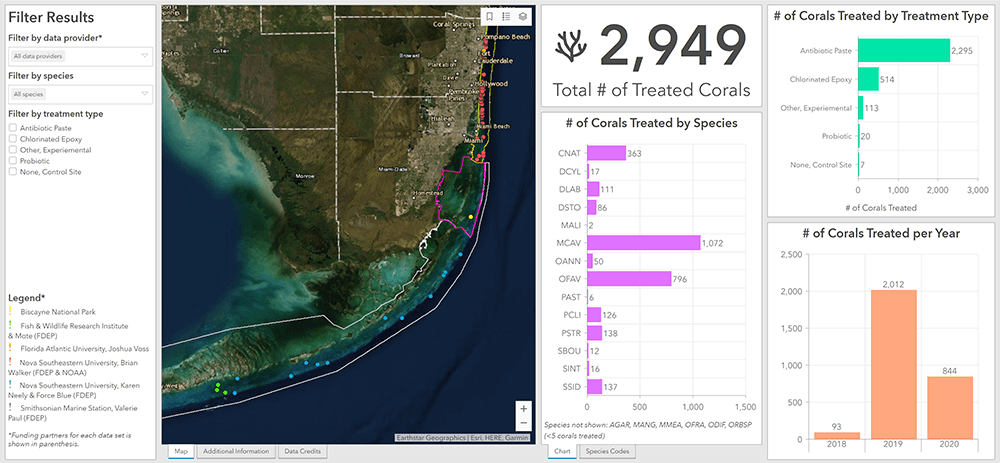

Interventions and Treatments

Scientists and resource managers are coordinating interventions and treatments with the goal to slow or stop the spread of stony coral tissue loss disease. The most urgent needs are at the disease front in the Lower Keys. Strategies include colony-specific interventions to prevent mortality of the most important corals, efforts to reduce the pathogen load, and salvage of selected colonies to prevent the loss of the diversity and genetic structure of the corals.

Saving the Exceptional Coral's in Florida's Coral Reef Ecosystem Conservation Area

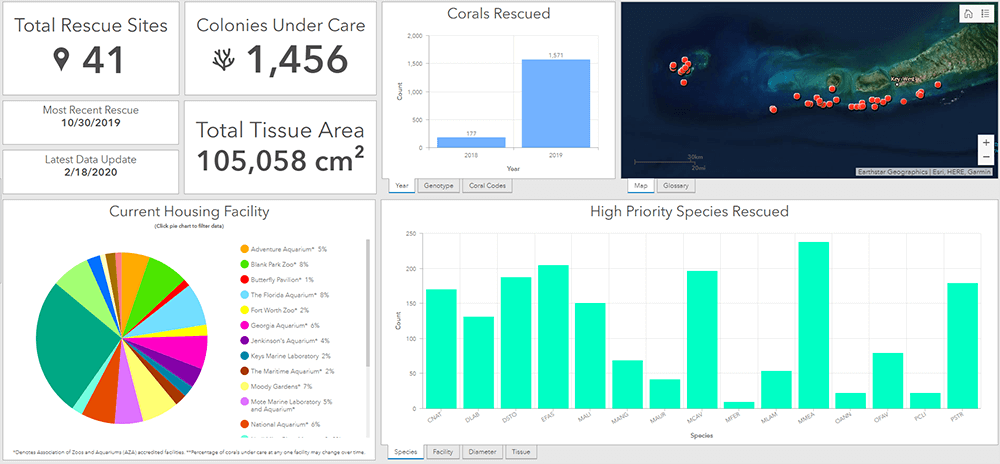

Coral Rescue

In December 2018, the Association of Zoos and Aquariums joined the collaborative response to stony coral tissue loss disease. As part of the AZA-Florida Reef Tract Rescue Project, facilities hold susceptible coral colonies harvested from the Florida Keys and Dry Tortugas National Park for restoration purposes.

AZA Holding Facilities

- Adventure Aquarium, New Jersey

- Blank Park Zoo, Iowa

- Butterfly Pavilion, Colorado

- Columbus Zoo and Aquarium, Ohio

- Disney's Animal Science and Environment, Florida

- The Florida Aquarium, Florida

- Fort Worth Zoo, Texas

- Georgia Aquarium, Georgia

- Jenkinson's Aquarium, New Jersey

- Maritime Aquarium at Norwalk, Connecticut

- Moody Gardens, Texas

- Mote Marine Laboratory and Aquarium, Florida

- National Aquarium, Maryland

- National Mississippi River Museum & Aquarium, Iowa

- Omaha's Henry Doorly Zoo, Nebraska

- Riverbanks Zoo & Garden, South Carolina

- SEA LIFE Michigan Aquarium, Michigan

- SeaWorld Orlando, Florida

- Texas State Aquarium, Texas

Ballast Water Best Management Practices to reduce the likelihood of transporting pathogens that may spread stony coral tissue loss disease

At the request of NOAA, the United States Coast Guard is considering options to mitigate the potential factors that may be contributing to the spread of stony coral tissue loss disease including the potential transfer of pathogens in ballast water. Current federal regulations specify that certain ships conduct ballast water exchanges beyond 200 nautical miles of any shore prior to discharge of ballast water within U.S. waters. In additional, vessels are encouraged to use their existing ballast water management systems to treat ballast water prior to release. Outside of U.S. waters, unmanaged ballast water should not be released within either 12 nautical miles of any shore or water less than 200 meters in depth.

Assessing effectiveness of treatments

Probiotic Experiments

Scientists are testing the theory that probiotics may bolster coral resistance and recovery. Researchers with the Smithsonian and the University of Florida are using healthy corals taken from Florida waters to develop probiotics that could slow or prevent disease progression. They isolate potentially beneficial microorganisms (probiotics) from more disease-resistant coral genotypes and test them on great star coral (Montastraea cavernosa), one of the species susceptible to stony coral tissue loss disease.

Preliminary results suggest that these good bacteria on healthy corals may help defend their host from infection and that they are a plausible treatment for diseased corals. Additional experiments suggest that the beneficial effects of probiotic treatments may be transferable from probiotic-treated healthy corals to diseased corals, potentially allowing for simultaneous restoration and treatment efforts. Two field applications of a probiotic cocktail for great star coral (Montastraea cavernosa) have been pilot tested on reefs off Broward County using a topical paste and a bagging method. Probiotic treatments could have the potential to colonize corals and provide a more lasting protection, which would be immensely valuable to disease management efforts.

Restoration

In response to the decline in coral reef health, the Florida Keys region has become a world leader in coral reef restoration. Although local efforts have had success at small scales, restoration has not been able to keep up with the rate of decline. Using the best available restoration science, NOAA and partners will restore diverse, reef-building corals at seven reef sites within Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary that represent the iconic diversity and productivity of Florida Keys coral reefs. For the first time, NOAA will proactively intervene with natural conditions by removing nuisance and invasive species and introducing disease-resistant and climate-resilient corals.